This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: Among the Forces

Author: Henry White Warren

Release Date: May 9, 2005 [eBook #15807]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AMONG THE FORCES***

Fairies, fays, genii, sprites, etc., were once supposed to be helpful to some favored men. The stories about these imaginary beings have always had a fascinating interest. The most famous of these stories were told at Bagdad in the eleventh century, and were called The Arabian Nights' Entertainment. Then men were said to use all sorts of obedient powers, sorceries, tricks, and genii to aid them in getting wealth, fame, and beautiful brides.

But I find the realities of to-day far greater, more useful and interesting, than the imaginations of the past. The powers at work about us are far more kindly and powerful than the Slave of the Ring or of the Lamp.

The object of writing this series of papers about applications of powers to the service of man, their designed king, is manifold. I desire all my readers to see what marvelous provision the Father has made for his children in this their nursery and schoolhouse. He has always been trying to crowd on men more helps and blessings than they were willing to take. From the first mist that went up from the Garden the power of steam has been in every drop of water. Yet men carried their burdens. Since the first storm the swiftness and power of lightning have been trying to startle man into seeing that in it were speed and force to carry his thought and himself. But man still plodded and groaned under loads that might have been lifted by physical forces. I have seen in many lands men bringing to their houses water from the hills in heavy stone jars. Gravitation was meant to do that work, and to make it leap and laugh with pearly spray in every woman's kitchen. The good Father has offered his all-power on all occasions to all men.

I desire that the works of God should keep their designed relation to thought. He says, Consider the lilies; look into the heavens; number the stars; go to the ant; be wise; ask the beasts, the fowl, the fishes; or "talk even to the earth, and it showeth thee."

Every flower and star, rainbow and insect, was meant to be so provocative of thought that any man who never saw a human book might be largely educated. And every one of these thoughts is related to man's best prosperity and joy. He is a most regal king if he achieve the designed dominion over a thousand powerful servitors.

It is well to see that God's present actual powers in full play about us are vastly beyond all the dreams of Arabian imagination. It leads us to expect greater things of him hereafter. That human imagination could so dream is proof of the greatness of its Creator. But that he has actually surpassed those dreams is prophecy of more greatness to come.

I desire that my readers of this generation shall be the great thinkers and inventors of the next. There are amazing powers just waiting to be revealed. Draw aside the curtain. We have not yet learned the A B C of science. We have not yet grasped the scepters of provided dominion. Those who are most in the image and likeness of the Cause of these forces are most likely to do it.

A man once had a large field of wheat. He had toiled hard to clear the land, plow the soil, and sow the seed. The crop grew beautifully and was his joy by day and by night. But when it was just ready to head out it suddenly stopped growing for want of moisture. It looked as if all his hard work would be in vain. The poor farmer thought of his wife and children, who were likely to starve in the coming winter. He shed many tears, but they could not moisten one little stalk.

Suddenly he said, "I will water it myself." The field was a mile square, and it needed an inch of water over it all. He quickly figured out that there were 27,878,400 square feet in a square mile. On every twelve square feet a cubic foot of water was needed. A cubic foot of water weighs sixty-two and a third pounds. Hence it would require 74,754 tons of water. To draw this amount 74,754 teams, each drawing a ton, would be required. But they would tramp the wheat all down. Besides, the nearest water in sufficient quantity was the ocean, one thousand miles away over the mountains. It would take three months to make the journey. And, worse than all else, the water of the ocean is so salt that it would ruin the crop.

Alas! there were three impossibilities--so many teams, so many miles, so long time--and two ruins if he could overcome the impossibilities--trampling down the wheat and bringing so much salt. Alas, alas! what could he do but see the poor wheat die of thirst and his poor wife and children die of hunger?

Suddenly he determined to ask the sun to help him. And the sun said he would. That was a very little thing for such a great body to do. So he heated the air over the ocean till it became so thirsty that it drank plenty of water, choosing only the sweet fresh water and leaving all the salt in the ocean. Then the warm air rose, because the heat had expanded it and made it lighter, and the other air rushed down the mountains all over that side of the continent to take its place. Then the warm air went landward in an upper current and carried its load of water in great piles and mountains of clouds; it lifted them over the great ranges of mountains and rained down its thousands of tons of sweet water a thousand miles from the sea, so gently that not a stalk of wheat was trampled down, nor was a single root made acrid by any taste of brine.

Besides the precious drink the sun brought the most delicate food for the wheat. There was carbonic acid, that makes soda water so delicious, besides oxygen, that is so stimulating, nitrogen, ammonia, and half a dozen other things that are so nutritious to growing plants.

Thus the wheat grew up in beauty, headed out abundantly, and matured perfectly. Then the farmer stopped weeping for laughter, and in his joy he remembered to thank, not the sun, nor the wind, but the great One who made them both.

There was once a man who had thousands of acres of mighty forests in the distant mountains. They were valueless there, but would be exceedingly valuable in the great cities hundreds of miles away, if he could only find any power to transport them thither. So he looked for a team that could haul whole counties of forests so many miles. He saw that the sun drew the greatest loads, and he asked it to help him. And the sun said that was what he was made for; he existed only to help man. He said that he had made those great forests to grow for a thousand years so as to be ready for man when he needed them, and that he was now ready to help move them where they were wanted.

So he told the man who owned the forest that there was a great power, which men called gravitation, that seemed to reside in the center of the earth and every other world, but that it worked everywhere. It held the stones down to the earth, made the rain fall, and water to run down hill; and if the man would arrange a road, so that gravitation and the sun could work together, the forest would soon be transported from the mountains to the sea.

So the man made a trough a great many miles long, the two sides coming together like a great letter V. Then the sun brought water from the sea and kept the trough nearly full year after year. The man put into it the lumber and logs from the great forests, and gravitation pulled the lumber and water ever so swiftly, night and day, miles away to the sea.

How I have laughed as I have seen that perpetual stream of lumber and timber pour out so far from where the sun grew them for man. For the sun never ceased to supply the water, and gravitation never ceased to pull.

This man who relentlessly cut down the great forests never said, "How good the sun is!" nor, "How strong is gravitation!" but said continually, "How smart I am!"

Holland is a land that is said to draw twenty feet of water. Its surface is below sea level. Since 1440 they have been recovering land from the sea. They have acquired 230,000 acres in all. Fifty years ago they diked off 45,000 acres of an arm of the sea, called Haarlem Meer, that had an average depth of twelve and three quarters feet of water, and proposed to pump it out so as to have that much more fertile land. They wanted to raise 35,000,000 tons of water a month a distance of ten feet, to get through in time. Who could work the handle?

The sun would evaporate two inches a year, but that was too slow. So they used the old force of the sun, reservoired in former ages. Coal is condensed sunshine, still keeping all the old light and power. By a suitable engine they lifted 112 tons ten feet at every stroke, and in 1848, five years after they began to apply old sun force, 41,675 acres were ready for sale and culture.

The water that accumulates now, from rain and infiltration, is lifted out by the sun force as exhibited in wind on windmills. They groaningly work while men sleep.

The Netherlandish engineers are now devising plans to pump out the Zuyder Zee, an area of two thousand square miles. There is plenty of power of every kind for anything, material, mental, spiritual. The problem is the application of it. The thinker is king.

This is only one instance of numberless applications of old sun force. In this country coal does more work than every man, woman, and child in the whole land. It pumps out deep mines, hoists ore to the surface, speeds a thousand trains, drives great ships, in face of waves and winds, thousands of miles and faster than transcontinental trains. It digs, spins, weaves, saws, planes, grinds, plows, reaps, and does everything it is asked to do. It is a vast reservoir of force, for the accumulation of which thousands of years were required.

At Foo-Chow, China, there is a stone bridge, more than a mile long, uniting the two parts of the city. It is not constructed with arches, but piers are built up from the bottom of the river and great granite stringers are laid horizontally from pier to pier. I measured some of these great stone stringers, and found them to be three feet square and forty-five feet long. They weigh over thirty tons each.

How could they be lifted, handled, and put in place over the water on slender piers? How was it done? There was no Hercules to perform the mighty labor, nor Amphion to lure them to their place with the music of his golden lyre.

Tradition says that the Chinese, being astute astronomers, got the moon to do the work. It was certainly very shrewd, if they did. Why not use the moon for more than a lantern? Is it not a part of the "all things" over which man was made to have dominion?

Well, the Chinese engineers brought the great granite blocks to the bridge site on floats, and when the tide lifted the floats and stones they blocked up the stones on the piers and let the floats sink with the outgoing tide. Then they blocked up the stones on the floats again, and as the moon lifted the tides once more they lifted the stones farther toward their place, until at length the work was done for each set of stones.

Dear, good moon, what a pull you have! You are not merely for the delight of lovers, pleasant as you are for that, but you are ready to do gigantic work.

No wonder that the Chinese, as they look at the solid and enduring character of that bridge, name it, after the poetic and flowery habit of the country, "The Bridge of Ten Thousand Ages."

Years ago, before there were any railroads, New York city had thousands of tons of merchandise it wished to send out West. Teams were few and slow, so they asked the moon to help. It was ready; had been waiting thousands of years.

We shall soon see that it is easy to slide millions of tons of coal down hill, but how could we slide freight up from New York to Albany?

It is very simple. Lift up the lower end of the river till it shall be down hill all the way to Albany. But who can lift up the end of the river? The moon. It reaches abroad over the ocean and gathers up water from afar, brings it up by Cape Hatteras and in from toward England, pours it in through the Narrows, fills up the great harbor, and sets the great Hudson flowing up toward Albany. Then men put their big boats on the current and slide up the river. Six hours later the moon takes the water out of the harbor and lets other boats slide the other way.

New York itself has made use of the moon to get rid of its immense amount of garbage and sewage. It would soon breed a pestilence, and the city be like the buried cities of old; but the moon comes to its aid, and carries away and buries all this foul breeder of a pestilence, and washes all the harbor and bay with clean floods of water twice a day. Good moon! It not only lights, but works.

The tide in New York Harbor rises only about five feet; up in the Bay of Fundy it ramps, rushes, raves, and rises more than fifty feet high.

In former times men used to put mill wheels into the currents of the tides; when they rushed into little bays and salt ponds they turned the wheels one way; when out, the other.

"We for whose sake all Nature stands,

And stars their courses move."

Do the stars, that are so far away and seem so small, send us any help? Assuredly. Nothing exists for itself. All is for man.

Magnetism tells the sailor which way he is going. Stars not only do this, when visible, but they also tell just where on the round globe he is. A glance into their bright eyes, from a rolling deck, by an uneducated sailor, aided by the tables of accomplished scholars, tells him exactly where he is--in mid Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, Arctic, or Antarctic Ocean, or at the mouth of the harbor he has sought for months. We lift up our eyes higher than the hills. Help comes from the skies.

This help was started long since, with providential foresight and care. Is he steering by the North Star? A ray of guidance was sent from that lighthouse in the sky half a century before his need, that it might arrive just at the critical time. It has been ever since on its way.

The stars give us, on land and sea, all our reliable standards of time. There is no other source. They are reliable to the hundredth part of a second.

The Italian physicians, in their ignorance of the origin of a disease, named it the influenza, because they imagined that it came from the influence of the stars. No! There is nothing malign in the sweet influences of the Pleiades.

The stars are of special use as a mental gymnasium. On their lofty bars and trapezes the mind can swing itself higher and farther than on any other material thing. Infinity and omnipotence are factors in their problems. They also fill the soul of the rapt beholder with adoring wonder. They are the greatest symbols of the unweariableness of the power and of the minuteness of the knowledge of God. He calleth all their millions by name, and for the greatness of his power not one faileth to come.

Number the stars of a clear Eastern sky, if you are able. So multitudinous and enduring shall the influence of one good man be.

Suppose one has been at sea a month. He has tacked to every point of the compass, been driven by gales, becalmed in doldrums. At length Euroclydon leaps on him, and he lets her drive. And when for many days and nights neither sun nor stars appear, how can he tell where he is, which way he drives, where the land lies?

There is an insensible ocean. No sense detects its presence. It has gulf streams that flow through us, storms whose waves engulf us, but we feel them not. There are various intensities of its power, the north end of the world not having half as much as the south. There are two places in the north half of the world that have greater intensity than the rest, and only one in the south. It looks as if there were unsoundable depths in some places and shoals in others.

The currents do not flow in exactly the same direction all the time, but their variations are within definite limits.

How shall we detect these steady currents when wind and waves are in tumultuous confusion? They are always present. No winds blow them aside, no waves drench their subtle fire, no mountains make them swerve. But how shall we find them?

Float a bit of magnetic ore in a pail of water, or suspend a bit of magnetized steel by a thread, and these currents make the ore or needle point north and south. Now let waves buffet either side, typhoons roar, and maelstroms whirl; we have, out of the invisible, insensible sea of magnetic influence, a sure and steady guide. Now we can sail out of sight of headlands. We have in the darkness and light, in calm and storm, an unswerving guide. Now Columbus can steer for any new world.

Does not this seem like a spiritual force? Lodestone can impart its qualities to hard steel without the impairment of its own power. There is a giving that does not impoverish, and a withholding that does not enrich.

Wherever there is need there is supply. The proper search with appropriate faculties will find it. There are yet more things in heaven and earth than are dreamed of in our philosophy.

The Germans imagine that they have fairy kobolds, sprites, and gnomes which play under ground and haunt mines. I know a real one. I will give you his name. It is called "Gravitation." The name does not sound any more fairylike than a sledge hammer, but its nature and work are as fairylike as a spider's web. I will give samples of his helpful work for man.

In the mountains about Saltzburg, south of Munich, are great thick beds of solid salt. How can they get it down to the cities where it is needed? Instead of digging it out, and packing it on the backs of mules for forty miles, they turn in a stream of water and make a little lake which absorbs very much salt--all it can carry. Then they lay a pipe, like a fairy railroad, and gravitation carries the salt water gently and swiftly forty miles, to where the railroads can take it everywhere. It goes so easily! There is no railroad to build, no car to haul back, only to stand still and see gravitation do the work.

How do they get the salt and water apart? O, just as easily. They ask the wind to help them. They cut brush about four feet long, and pile it up twenty feet high and as long as they please. Then a pipe with holes in it is laid along the top, the water trickles down all over the loose brush, and the thirsty wind blows through and drinks out most of the water. They might let on the water so slowly that all of it would be drunk out by the wind, leaving the solid salt on the bushes. But they do not want it there. So they turn on so much water that the thirsty wind can drink only the most of it, and the rest drops down into great pans, needing only a little evaporation by boiling to become beautiful salt again, white as the snows of December.

There are other minerals besides salt in the beds in the mountains, and, being soluble in water, they also come down the tiny railroad with musical laughter. How can we separate them, so that the salt shall be pure for our tables?

The other minerals are less avaricious of water than salt, so they are precipitated, or become solid, sooner than salt does. Hence with nice care the other minerals can be left solid on the bushes, while the salt brine falls off. Afterward pure water can be turned on and these other minerals can be washed off in a solution of their own. No fairies could work better than those of solution and crystallization.

At Hutchinson, Kan., there are great beds of solid rock salt four hundred feet below the surface. Men want to get and use two thousand barrels a day. How shall they get it to the top of the ground? They might dig a great well--or, as the miners say, sink a shaft--pump out the water, go down and blast out the salt, and laboriously haul it up in defiance of gravitation. No; that is too hard. Better ask this strong gravitation to bring it up.

But does it work down and up? Did any one ever know of gravitation raising anything? O yes, many things. A balloon may weigh as much as a ton, but when inflated it weighs less than so much air; so the heavier air flows down under and shoulders it up. When a heavy weight and a light one are hung over a pulley, the light one goes up because gravity acts more on the other. Water poured down a long tube will rise if the tube is bent up into a shorter arm.

Exactly. So we bore a four-inch hole down to the salt and put in an iron tube.

We do not care about the water. It is no bother. Then inside of this tube we put a two-inch tube that is a few feet higher. Now pour water down the small longer tube. It saturates itself with salt, and comes flowing over the top of the shorter tube as easily as water runs down hill. Multiply the wells, dry out the water, and you have your two thousand barrels of salt lifted every day--just as easy as thinking!

We want a steady, unswerving force that will pull our clock hands with an exact motion day and night, year in and year out. We hang up a string, and ask gravitation to take hold and pull. We put on some lead or brass for a handle, to take hold of. It takes hold and pulls, unweariedly, unvaryingly, and ceaselessly.

It turns single water-wheels with a power of more than twelve hundred horses.

It holds down houses, so that they are not blown away. It was made to serve man, and it works without a grumble.

Thus the higher force in nature always prevails over the lower, and the greater amount over the less amount of the same force. What is the highest force?

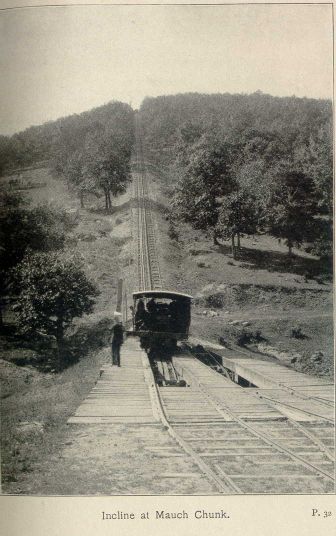

Far back in the hills west of Mauch Chunk, Pa., lie great beds of coal. They were made under the sea long ages ago, raised up, roofed over by the Allegheny Mountains, and kept waiting as great reservoirs of power for the use of man.

But how can these mountains be gotten to the distant cities by the sea? Faith in what power can say to these mountains, "Be thou removed far hence, and cast into the sea?" It is easy.

Along the winding sides of the mountains have been laid two rails like steel ribbons for a dozen miles, from the coal beds to water and railroad transportation. Put a half dozen loaded cars on the track, and with one man at the brake, lest gravitation should prove too willing a helper, away they go, through the springtime freshness or the autumn glory, spinning and singing down to the point of universal distribution.

On one occasion the brake for some reason would not work. The cars just flew like an arrow. The man's hair stood up from fright and the wind. Coming to a curve the cars kept straight on, ran down a bank, dashed right into the end of a house and spilled their whole load in the cellar. Probably no man ever laid in a winter's supply of coal so quickly or so undesirably.

But how do we get the cars back? It is pleasant sliding down hill on a rail, but who pulls the sled back? Gravitation. It is just as willing to work both ways as one way.

Think of a great letter X a dozen miles long.

Lay it down on the side against three or four rough hills. Bend the X till it will fit the curves and precipices of these hills. That is the double track. Now when loaded cars have come down one bar of the X by gravity, draw them up by a sharp incline to the upper end of the other bar, and away they go by gravity to the other end. Draw them up one more incline, and they are ready to take a new load and buzz down to the bottom again.

I have been riding round the glorious mountain sides in a horseless, steamless, electricityless carriage, and been delighted to find hundreds of tons of coal shooting over my head at the crossings of the X, and both cars were drawn in opposite directions by the same force of gravity in the heart of the earth.

If you do not take off your hat and cheer for the superb force of gravitation, the wind is very apt to take it off for you.

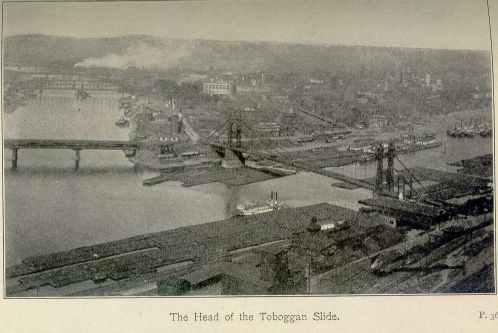

Pittsburg has 5,000,000 tons of coal every year that it wishes to send South, much of it as far as New Orleans--2,050 miles. What force is sufficient for moving such great mountains so far? Any boy may find it.

Tie a stone to the end of a string, whirl it around the finger and feel it pull. How much is the pull? That depends on the weight of the stone, the length of the string, and the swiftness of the whirl. In the case of David's sling it pulled away hard enough to crash into the head of Goliath. Suppose the stone to be as big as the earth (8,000 miles in diameter), the length of the string to be its distance from the sun (92,500,000 miles), and the swiftness of flight the speed of the earth in its orbit (1,000 miles a minute). The pull represents the power of gravitation that holds the earth to the sun.

If we use steel wires instead of gravitation for this purpose, each strong enough to support half a score of people (1,500 pounds), how many would it take? We would need to distribute them over the whole earth: from pole to pole, from side to side, over all the land and sea. Then they would need to be so near together that a mouse could not run around among them.

Here is a measureless power. Can it be gotten to take Pittsburgh coal to New Orleans? Certainly; it was made to serve man. So the coal is put on great flatboats, 36 x 176 feet, a thousand tons to a boat, and gravitation takes the mighty burden down the long toboggan slide of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers to the journey's end. How easy!

One load sent down was 43,000 tons. The flatboats were lashed together as one solid boat covering six and one half acres, more space than a whole block of houses in a city, with one little steamboat to steer. There is always plenty of power; just belt on for anything you want done. This is only one thing that gravitation does for man on these rivers. And there are many rivers. They serve the savage on his log and the scientist in his palace steamer with equal readiness.

The Slave of the Ring could take Aladdin into a cave of wealth, and by speaking the words, "Open Sesame," Ali Baba was admitted into the cave that held the treasures of the forty thieves. But that is very little. I have just come from a cave in Virginia City, Nev., from which men took $120,000,000.

In following the veins of silver the miners went down 3,500 feet--more than three fifths of a mile. There it was fearfully hot, but the main trouble was water. They had dug a deep, deep well. How could they get the water out? Pumps were of no use. A column of water one foot square of that height weighs 218,242 pounds. Who could work the other end of the pump handle?

They thought of evaporating the water and sending it up as steam. But it was found that it would take an incredible amount of coal. They thought of separating it into oxygen and hydrogen, and then its own lightness would carry it up very quickly. But they had no power that would resolve even quarts into their ultimate elements, where tons would be required.

So they asked gravitation to help them. It readily offered to do so. It could not let go its hold of the water in the mine, nor anywhere else, for fear everything would go to pieces, but it offered to overcome force with greater force. So it sent the men twenty miles away in the mountains to dig a ditch all the way to the mine, and then gravitation brought water to a reservoir four hundred feet above the mouth of the mine. Now a column of this water one foot square can be taken from this higher reservoir down to the bottom of the mine and weigh 25,000 pounds more than a like column that comes from the bottom to the top. This extra 25,000 pounds is an extra force available to lift itself and the other water out of the deep well, and they turn the greater force into a pump and work it in the cylinder as if it were steam. It lifts not only the water that works the pump, but the other water also out of the mine by gravitation. So man gets the water out by pouring more water in.

Since the time of David many boys have swung pebbles by a string, or sling, and felt the pull of what we call a centrifugal (center-fleeing) force. David utilized it to one good purpose. Goliath was greatly surprised; such a thing never entered his head before. Whether a stone or an idea enters one's head depends on the kind of head he has.

We utilize this force in many ways now. Some boys swing a pail of milk over their heads, and if swung fast enough the centrifugal force overcomes the force of gravitation, and the milk does not fall. That is not utilizing the force. It often terrorizes the careful mother, anxious for the safety of the milk.

But in the arts of practical life we do utilize this force, which is only inertia.

Once it took a long time for molasses to drain out of a hogshead of damp sugar. Now it is put into a great tub, with holes in the side, which is made to revolve rapidly, and the molasses flies out. In the best laundries clothes are not wrung out, to the great damage of tender fabrics, but are put into such a tub and whirled nearly dry. So fifty yards of woolen cloth just out of the dye vat--who could wring it? It is coiled in a tub called a wizard, and whirled.

Muddy water is put through a process called clarification. It is the same, except that there are no holes in the vessel. The heavier particles of dirt, that would settle in time, take the outside, leaving perfectly clean water in the middle. A perpendicular perforated pipe, with a faucet below, drains off all the clear water and leaves all the mud. Milk is brought in from the milking and put into a separator; whirl it, and the heavier milk takes the outside of the whirling mass, and the lighter cream can be drawn off from the middle. It is far more perfectly separated than by any skimming.

A rotary snowplow slices off two feet of a ten-foot drift at each revolution, and by centrifugal force flings it out of the cutting with a speed that a hundred navvies or dagos cannot equal.

A thousand acres of land on Cape Cod were once blown away. This wind excavation was ten feet deep. It was not an extraordinary wind, but extraordinary land. It was made of rock ground up into fine sand by the waves on the shore.

In all the deserts of the world the wind blows the itinerant sand on its far journeys. If the wind is moderate it heaps the sand up into little hills, some of them six hundred feet high, around any obstruction, and then blows the sand up the slanting face of the hill and over the top, where it falls out of the wind on the leeward side. In this way the hill is always traveling. In North Carolina hills start inland, and travel right on, burying a house or farm if it be in the way, but resurrecting it again on the other side as the hill goes on. Anyone may see these hills at the south end of Lake Michigan, as he approaches Chicago, west of San Francisco, all along up the Columbia River--the sand having come on the wings of the wind from the coast.

But to see the whole visible world on a march one needs to go to a really large desert. The Pyramids and the Sphinx have been partly buried, and parts of the valley of the Nile threatened, by hordes of sand hills marching in from the desert; cities have been buried and harbors filled up. Many of the harbors of the ancient civilizations are mere miasmatic marshes now. This is partly in consequence of the silt brought in by the rivers; but where the rivers do not flow in it is because the sand blows in along the shore. Harbors are especially endangered when their protection from the waves consists of a bank of sand, as on Cape Cod and the Sandy Hook below the Narrows of the harbor of New York.

How can man combat part of the continent on the move, driven by the ceaseless powers of the air? By a humble plant or two. The movement of the sand hills that threaten to destroy the marvelous beauty of the grounds of the Hotel del Monte at Monterey is stopped by planting dwarf pines. The sand dunes that prevent much of Holland from being reconquered by the sea are protected with great care by willows, etc., and the coast sands of parts of eastern France have been sown with sea pine and broom.

The tract of a thousand acres on Cape Cod had been protected by humble beach grass. Some careless herder let the cows eat it in places, and away went part of a township. It is now a punishable crime on Cape Cod to destroy beach grass.

This refers to more than stump speech-making. The old Romans drove through solid rock numerous tunnels similar to the one for draining Lago de Celano, fifty miles east of Rome. This one was three and a half miles long, through solid rock, and every chip cost a blow of a human arm to dislodge it. Of course the process was very slow.

We do works vastly greater. We drive tunnels three times as long for double-track railways through rock that is held down by an Alp. We use common air to drill the holes and a thin gas to break the rock. The Mont Cenis tunnel required the removal of 900,000 cubic yards of rock. Near Dover, England, 1,000,000,000 tons of cliff were torn down and scattered over fifteen acres in an instant. How was it done? By gas.

There are a dozen kinds of solids which can be handled--some of them frozen, thawed, soaked in water, with impunity--but let a spark of fire touch them and they break into vast volumes of uncontrollable gas that will rend the heart out of a mountain in order to expand.

Gunpowder was first used in 1350; so the old Romans knew nothing of its power. They flung javelins a few rods by the strength of the arm; we throw great iron shells, starting with an initial velocity of fifteen hundred feet a second and going ten miles. The air pressure against the front of a fifteen-inch shell going at that speed is 2,865 pounds. That ton and a half of resistance of gas in front must be much more than overcome by gas behind.

But the least use of explosives is in war; not over ten per cent is so used. The Mont Cenis tunnel took enough for 200,000,000 musket cartridges. As much as 2,000 kegs have been fired at once in California to loosen up gravel for mining, and 23 tons were exploded at once under Hell Gate, at New York.

How strong is this gas? As strong as you please. Steam is sometimes worked at a pressure of 400 pounds to the inch, but not usually over 100 pounds. It would be no use to turn steam into a hole drilled in rock. The ordinary pressure of exploded gas is 80,000 pounds to the square inch. It can be made many times more forceful. It works as well in water, under the sea, or makes earthquakes in oil wells 2,000 feet deep, as under mountains.

The wildest imagination of Scheherezade never dreamed in Arabian Nights of genii that had a tithe of the power of these real forces. Her genii shut up in bottles had to wait centuries for some fisherman to let them out.

"Sacra fames auri." The hunger for gold, which in men is called accursed, in metals is justly called sacred.

In all the water of the sea there is gold--about 400 tons in a cubic mile--in very much of the soil, some in all Philadelphia clay, in the Pactolian sands of every river where Midas has bathed, and in many rocks of the earth. But it is so fine and so mixed with other substances that in many cases it cannot be seen. Look at the ore from a mine that is giving its owners millions of dollars. Not a speck of gold can be seen. How can it be secured? Set a trap for it. Put down something that has an affinity--voracious appetite, unslakable thirst, metallic affection--for gold, and they will come together.

We have heard of potable gold--"potabile aurum." There are metals to which all gold is drinkable. Mercury is one of them. Cut transverse channels, or nail little cleats across a wooden chute for carrying water. Put mercury in the grooves or before the cleats, and shovel auriferous gravel and sand into the rushing water. The mercury will bibulously drink into itself all the fine invisible gold, while the unaffectionate sand goes on, bereaved of its wealth.

Put gold-bearing quartz under an upright log shod with iron. Lift and drop the log a few hundred times on the rock, until it is crushed so fine that it flows over the edge of the trough with constantly going water, and an amalgam of mercury spread over the inclined way down which the endusted water flows will drink up all the gold by force of natural affection therefor.

Neither can the gold be seen in the mercury. But it is there. Squeeze the mercury through chamois skin. An amalgam, mostly gold, refuses to go through. Or apply heat. The mercury flies away as vapor and the gold remains.

If thou seekest for wisdom as for silver, and searchest for her as for hid treasure, thou shalt find.

A little boy had a silver mug that he prized very highly, as it was the gift of his grandfather. The boy was not born with a silver spoon in his mouth, but, what was much better, he had a mug often filled with what he needed.

One day he dipped it into a glass jar of what seemed to him water, and letting go of it saw it go to the bottom. He went to find his father to fish it out for him. When he came back his heavy solid mug looked as if it were made of the skeleton leaves of the forest when the green chlorophyll has decayed away in the winter and left only the gauzy veins and veinlets through which the leaves were made. Soon even this fretwork was gone, and there was no sign of it to be seen. The liquid had eaten or drank the solid metal up, particle by particle. The liquid was nitric acid.

The poor little boy had often seen salt, and especially sugar, absorbed in water, but never his precious solid silver mug, and the bright tears rolled down his cheeks freely.

But his father thought of two things: First, that the blue tint told him that the jeweler had sold for silver to the grandfather a mug that was part copper; and secondly, that he would put some common salt into the nitric acid--which it liked so much better than silver that it dropped the silver, just as a boy might drop bread when he sought to fill his hands with cake.

So the father recovered the invisible silver and made it into a precious mug again.

A man was waked up one night in a strange house by a noise he could not understand. He wanted a light, and wanted it very much, but he had no matches that would take fire by the heat of friction. He knew of many other ways of starting a fire. If water gets to the cargo of lime in a vessel it sets the ship on fire. It is of no use to try to put it out by water, for it only makes more heat. He knew that dried alum and sugar suitably mixed would burst into flame if exposed to the air; that nitric acid and oil of turpentine would take fire if mixed; that flint struck by steel would start fire enough to explode a powder magazine; and that Elijah called down from heaven a kind of fire that burned twelve "barrels" of water as easily as ordinary water puts out ordinary fire. But he had none of these ways of lighting his candle at hand--not even the last.

So he took a bit of potassium metal, bright as silver, out of a bottle of naphtha, put it in the candle wick, touched it with a bit of dripping ice, and so lighted his candle.

The potassium was so avaricious of oxygen that it decomposed the water to get it. Indeed, it was a case of mutual affection. The oxygen preferred the company of potassium to that of the hydrogen in the water, and went to it even at the risk of being burned.

I was so interested in seeing a bit of silver-like metal and water take fire as they touched that I forgot all about the occasion of the noise.

Benjamin C. B. Tilghman, of Philadelphia, once went into the lighthouse at Cape May, and, observing that the window glass was translucent rather than transparent, asked the keeper why he put ground glass in the windows. "We do not," said the keeper. "We put in the clear glass, and the wind blows the sand against it and roughens the outer surface like ground glass." The answer was to him like the falling apple to Newton. He put on his thinking cap and went out. It was better than the cap of Fortunatus to him. He thought, "If nature does this, why cannot I make a fiercer blast, let sand trickle into it, and so hurl a million little hammers at the glass, and grind it more swiftly than we do on stones with a stream of wet sand added?"

He tried jets of steam and of air with sand, and found that he could roughen a pane of glass almost instantly. By coating a part of the glass with hot beeswax, applied with a brush, through a stencil, or covering it with paper cut into any desired figures, he could engrave the most delicate and intricate patterns as readily as if plain. Glass is often made all white, except a very thin coating of brilliant colored glass on one side. This he could cut through, leaving letters of brilliant color and the general surface white, or vice versa.

Seal cutting is a very delicate and difficult art, old as the Pharaohs. Protect the surface that is to be left, and the sand blast will cut out the required design neatly and swiftly.

There is no known substance, not even corundum, hard enough to resist the swift impact of myriads of little stones.

It will cut more granite into shape in an hour than a man can in a day.

Surely no one will be sorry to learn that General Tilghman sold part of his patents, taken out in October, 1870, for $400,000, and receives the untold benefits of the rest to this day. So much for thinking.

Nature gives thousands of hints. Some can take them; some can only take the other thing. The hints are greatly preferred by nature and man.

The forces of creation are yet in full play. Who can direct them? Rewards greater than Tilghman's await the thinker. We are permitted not only to think God's thoughts after him, but to do his works. "Greater works than these that I do shall he do who believeth on me," says the Greatest Worker. Great profit incites to do the work noted below.

Carbon as charcoal is worth about six cents a bushel; as plumbago, for lead pencils or for the bicycle chain, it is worth more; as diamond it has been sold for $500,000 for less than an ounce, and that was regarded as less than half its value. Such a stone is so valuable that $15,000 has been spent in grinding and polishing its surface. The glazier pays $5.00 for a bit of carbon so small that it would take about ten thousand of them to make an ounce.

Why is there such a difference in value? Simply arrangement and compactness. Can we so enormously enhance the value of a bushel of charcoal by arrangement and compression? Not very satisfactorily as yet. We can apply almost limitless pressure, but that does not make diamonds. Every particle must go to its place by some law and force we have not yet attained the mastery of.

We do not know and control the law and force in nature that would enable us to say to a few million bricks, stones, bits of glass, etc., "Fly up through earth, water, and air, and combine into a perfect palace, with walls, buttresses, towers, and windows all in exact architectural harmony." But there is such a law and force for crystals, if not for palaces. There is wisdom to originate and power to manage such a force. It does not take masses of rock and stick them together, nor even particles from a fluid, but atoms from a gas. Atoms as fine as those of air must be taken and put in their place, one by one, under enormous pressure, to have the resulting crystal as compact as a diamond.

The force of crystallization is used by us in many inferior ways, as in making crystals of rock candy, sulphur, salt, etc., but for the making of diamonds it is too much for us, except in a small way.

While we cannot yet use the force that builds large white diamonds we can use the diamonds themselves. Set a number of them around a section of an iron tube, place it against a rock, at the surface or deep down in a mine, cause it to revolve rapidly by machinery, and it will bore into the rock, leaving a core. Force in water, to remove the dust and chips, and the diamond teeth will eat their way hundreds of feet in any direction; and by examining the extracted core miners can tell what sort of ore there is hundreds of feet in advance. Hence, they go only where they know that value lies.

Ultimate atoms of matter are asserted to be impenetrable. That is, if a mass of them really touched each other, that mass would not be condensible by any force. But atoms of matter do not touch. It is thinkable, but not demonstrable, that condensation might go on till there were no discernible substance left, only force.

Matter exists in three states: solid, liquid, and gas. It is thought that all matter may be passed through the three stages--iron being capable of being volatilized, and gases condensed to liquids and solids--the chief difference of these states being greater or less distance between the constituent atoms and molecules. In gas the particles are distant from each other, like gnats flying in the air; in liquids, distant as men passing in a busy street; in solids, as men in a congregation, so sparse that each can easily move about. The congregation can easily disperse to the rarity of those walking in the street, and the men in the street condense to the density of the congregation. So, matter can change in going from solids to liquids and gases, or vice versa. The behavior of atoms in the process is surpassingly interesting.

Gold changes its density, and therefore its thickness, between the two dies of the mint that make it money. How do the particles behave as they snuggle up closer to each other?

Take a piece of iron wire and bend it. The atoms on the inner side become nearer together, those on the outside farther apart. Twist it. The outer particles revolve on each other; those of the middle do not move. They assume and maintain their new relations.

Hang a weight on a wire. It does not stretch like a rubber thread, but it stretches. Eight wires were tested as to their tensile strength. They gave an average of forty-five pounds, and an elongation averaging nineteen per cent of the total length. Then a wire of the same kind was given time to adjust itself to its new and trying circumstances. Forty pounds were hung on one day, three pounds more the next day, and so on, increasing the weights by diminishing quantities, till in sixty days it carried fifty-seven pounds. So it seems that exercise strengthened the wire nearly twenty-seven per cent.

While those atoms are hustling about, lengthening the wire and getting a better grip on one another, they grow warm with the exercise. Hold a thick rubber band against your lip--suddenly stretch it. The lip easily perceives the greater heat. After a few moments let it contract. The greater coldness is equally perceptible.

A wire suspending thirty-nine pounds being twisted ninety-five full turns lengthened itself one sixteen-hundredth of its length. Being further twisted by twenty-five turns it shortened itself one fourth of its previous elongation. During the twisting some sections took far more torsion than others. A steel wire supporting thirty-nine pounds was twisted one hundred and twenty times and then allowed to untwist at will. It let out only thirty-eight turns and retained eighty-two in the new permanent relation of particles. A wire has been known to accommodate itself to nearly fourteen hundred twists, and still the atoms did not let go of each other. They slid about on each other as freely as the atoms of water, but they still held on. It is easier to conceive of these atoms sliding about, making the wire thinner and longer, when we consider that it is the opinion of our best physicists that molecules made of atoms are never still. Masses of matter may be still, but not the constituent elements. They are always in intensest activity, like a mass of bees--those inside coming out, outside ones going in--but the mass remains the same.

The atoms of water behave extraordinarily. I know of a boiler and pipes for heating a house. When the fire was applied and the temperature was changed from that of the street to two hundred degrees, it was easy to see that there was a whole barrel more of it than when it was let into the boiler. It had been swollen by the heat, but it was nothing but water.

Mobile, flexible, and yielding as water seems to be, it has an obstinacy quite remarkable. It was for a long time supposed to be absolutely incompressible. It is nearly so. A pressure that would reduce air to one hundredth of its bulk would not discernibly affect water. Put a ton weight on a cubic inch of water; it does not flinch nor perceptibly shrink, yet the atoms of water do not fill the space they occupy. They object to being crowded. They make no objection to having other matter come in and possess the space unoccupied by them.

Air so much enjoys its free, agile state, leaping over hills and plains, kissing a thousand flowers, that it greatly objects to being condensed to a liquid. First we must take away all the heat. Two hundred and ten degrees of heat changes water to steam filling 1,728 times as much space. No amount of pressure will condense steam to water unless the heat is removed. So take heat away from air till it is more than two hundred degrees below zero, and then a pressure of about two hundred atmospheres (14.7 pounds each) changes common air to fluid. It fights desperately against condensation, growing hot with the effort, and it maintains its resilience for years at any point of pressure short of the final surrender that gives up to become liquid.

Perhaps sometime we shall have the pure air of the mountains or the sea condensed to fluid and sold by the quart to the dwellers in the city, to be expanded into air once more.

The marvel is not greater that gas is able to sustain itself under the awful pressure with its particles in extreme dispersion, than that what we call solids should have their molecules in a mazy dance and yet keep their strength.

Since this world, in power, fineness, finish, beauty, and adaptations, not only surpasses our accomplishment, but also is past our finding out to its perfection, it must have been made by One stronger, finer, and wiser than we are.

When a human breath, or the white jet of a steam whistle, or the black cough of a locomotive smokestack is projected into the air it is easy to see that the air is mobile. Its particles easily roll over one another in voluminously infolding wreaths. The same is seen in water. The crest of a wave falls over a portion of air, imprisoning it for a moment, and the mingled air and water of different densities prevent the light of the sun or sky from going straight down into the black depths and being lost, but by being reflected and turned back it shows like beautiful white lace, constantly created and dissolved with a thousandfold more beauty than any that ever came from human hands. All the three shifting elements of the swift creations are mobile. This seems to be the case because these elements are not solid. The particles have plenty of room to play about each other, to execute mazy dances and minuets with vastly more space than substance.

Extend the thought a little. Things that seem to us most solid are equally mobile. An iron wire seems solid. It is so; some parts much more so than others. The surface that has been in closest contact with the die as the wire was drawn through, reducing its size by one half, perhaps, is vastly more dense than the inner parts that have not been so condensed. File away one tenth of a wire, taking it all from the surface, and you weaken the tensile strength of the wire one half. But, dense and solid as this iron is, its particles are as mobile within certain limits as the particles of air. An electric message sent through a mile of wire is not anything transmitted; matter is not transferred, but the particles are set to dancing in wavy motion from end to end. Particles are leaping within ordered limits and according to regular laws as really as the clouds swirl and the air trembles into song through the throat of a singer. When a wire is made sensitive by electricity the breath of a child can make it vibrate from end to end, ensouled with the child's laughter or fancies. Nay, more, and far more wonderful, the wire will be sensitive to the number of vibrations of a certain note of music, and no receiver at the other end will gather up its sensitive tremblings unless it is pitched to the keynote of the vibrations sent. In this way eight sets of vibrations have been sent on one wire both ways at the same time, and no set of signals has in any way interfered with the completeness and audibility of the rest. Sixteen sets of waltzes were being performed at one and the same time by the particles of one wire without confusion. Because the air is transmitting the notes of an organ from the loft to the opposite end of the church, it is not incapable of bringing the sound of a voice in an opposite direction to the organist from the other end of the church.

The extreme mobility of steel is seen when the red-hot metal is plunged into water. Instantly every particle takes a new position, making it a hundredfold more hard than before it was heated. But these particles of transferred steel are still mobile. A man's razor does not cut smoothly. It is dull, or has a ragged edge that is more inclined to draw tears than cut hairs. He draws the razor over the tender palm of his hand a few times, rearranges the particles of the edge and builds them out into a sharper form. Then the razor returns to the lip with the dainty touch of a kiss instead of a saw. Or the tearful man dips the razor in hot water and the particles run out to make a wider blade and, of course, a thinner, sharper edge. Drop the tire of a wagon wheel into a circular fire. As the heat increases each particle says to its neighbor, "Please stand a little further off; this more than July heat is uncomfortable." So the close friends stand a little further apart, lengthening the tire an inch or two. Then, being taken out of the fire and put on the wheel and cooled, the particles snuggle up together again, holding the wheel with a grip of cold iron. Mobile and loose, with plenty of room to play, as the particles have, neither wire nor tire loses its tensile strength. They hold together, whether arms are locked around each other's waist, or hand clasps hand in farther reach. What change has come to iron when it has been made red or white hot? Its particles have simply been mobilized. It differs from cold iron as an army in barracks and forts differs from an army mobilized. Nothing has been added but movement. There is no caloric substance. Heat is a mode of motion. The particles of iron have been made to vibrate among themselves. When the rapidity of movement reaches four hundred and sixty millions of millions of vibrations per second it so affects the eye that we say it is red-hot. When other systems of vibration have been added for yellow, etc., up to seven hundred and thirty millions of millions for the violet, and all continue in full play, the eye perceives what we call white heat. It is a simple illustration of the readiness of seeming solids to vibrate with almost infinite swiftness.

I have been to-day in what is to me a kind of heaven below--the workshop of my much-loved friend, John A. Brashear, in Allegheny, Pa. He easily makes and measures things to one four-hundred-thousandth of an inch of accuracy. I put my hand for a few seconds on a great piece of glass three inches thick. The human heat raised a lump detectable by his measurements. We were testing a piece of glass half an inch thick; and five inches in diameter. I put my two thumbnails at the two sides as it rested on its bed, and could see at once that I had compressed the glass to a shorter diameter. We twisted it in so many ways that I said, "That is a piece of glass putty." And yet it was the firmest texture possible to secure. Great lenses are so sensitive that one cannot go near them without throwing them discernibly out of shape. It were easy to show that there is no solid earth nor immovable mountains. I came away saying to my friend, "I am glad God lets you into so much of his finest thinking." He is a mechanic, not a theologian. This foremost man in the world in his fine department was lately but a "greasy mechanic," an engineer in a rolling mill.

But for elasticity and mobility nothing approaches the celestial ether. Its vibrations reach into millions of millions per second, and its wave-lengths for extreme red light are only .0000266 of an inch long, and for extreme violet still less--.0000167 of an inch.

It is easier molding hot iron than cold, mobile things than immobile. This world has been made elastic, ready to take new forms. New creations are easy, for man, even--much more so for God. Of angels, Milton says:

"Thousands at his bidding speed,

And post o'er land and ocean without rest."

No less is it true of atoms. In him all things live and move. Such intense activities could not be without an infinite God immanent in matter.

Man's next realm of conquest is the celestial ether. It has higher powers, greater intensities, and quicker activities than any realm he has yet attempted.

When the emissory or corpuscular theory of light had to be abandoned a medium for light's interplay between worlds had to be conceived. The existence of an all-pervasive medium called the luminiferous ether was launched as a theory. Its reality has been so far demonstrated that but very few doubters remain.

What facts of its conditions and powers can be known? It differs almost totally from our conceptions of matter. Of the eighteen necessary properties of matter perhaps only one, extension, can be predicated of it. It is unlimited, all-pervasive; even where worlds are non-attractive, does not accumulate about suns or other bodies; has no structure, chemical relations, nor inertia; is not heatable, and is not cognizable by any of our present senses. Does it not take us one step toward an apprehension of the revealed condition of spirit?

Recall its actual activities. Two hundred and fifty-eight vibrations of air per second produce on the ear the sensation we call do, or C of the soprano scale; five hundred and sixteen give the upper C, or an octave above. So the sound runs up in air till, above, say, thirty-five thousand vibrations per second, there is plenty of sound inaudible to our ears. But not inaudible to finer ears. To them the morning stars sing together in mighty chorus:

"Forever singing as they shine,

'The hand that made us is divine.'"

Electricity has as great a variety of vibrations as sound. Since some kinds of electricity do not readily pass through space devoid of air, though light and heat do, it seems likely that some of the lower intensities and slower vibrations of electricity are not in ether but in air. Certainly some of the higher intensities are in ether. Between two hundred and four hundred millions of millions of vibrations of ether per second are the different sorts of heat. Between four hundred and eight hundred vibrations are the different colors of light. Beyond eight hundred vibrations there is plenty of light, invisible to our eyes, known as chemical rays and probably the Roentgen rays. Beyond these are there vibrations for thought-transference? Who knoweth?

These familiar facts are called up to show the almost infinite capacities and intensities of the ether. Matter is more forceful, as it is less dense. Rock is solid, and has little force except obstinate resistance. Steam is rarer and more forceful. Gases suddenly born of dynamite touched by fire in the rock under a mountain have the tremendous pressure of eighty thousand pounds to the square inch. Ether is so rare that its density, compared with water, is represented by a decimal fraction with twenty-seven ciphers before it.

When the worlds navigate this sea, do they plow through it as a ship through the waves, forcing them aside, or as a sieve letting the water through it? Doubtless the sieve is the better symbol. Certainly the vibrations flow through solid glass and most solid diamond. To be sure, they are a little hampered by the solid substance. The speed of light is reduced from one hundred and eighty thousand miles a second in space to one hundred and twenty thousand in glass. If ether can so readily go through such solids, no wonder that a spirit body could appear to the disciples, "the doors being shut."

Marvelous discoveries in the capacities of ether have been made lately. In 1842 Joseph Henry found that electric waves in the top of his house provoked action in a wire circuit in the cellar, through two floors and ceilings, without wire connections. More than twenty years ago Professor Loomis, of the United States coast survey, telegraphed twenty miles between mountains by electric impulses sent from kites. Last year Mr. Preece, the cable being broken, sent, without wires, one hundred and fifty-six messages between the mainland and the island of Mull, a distance of four and a half miles. Marconi, an Italian, has sent recognizable signals through seven or eight thick walls of the London post-office, and three fourths of a mile through a hill. Jagadis Chunder Bose, of India, has fired a pistol by an electric vibration seventy-five feet away and through more than four feet of masonry. Since brick does not elastically vibrate to such infinitesimal impulses as electric waves, ether must. It has already been proven that one can telegraph to a flying train from the overhead wires. Ether is a far better medium of transmission than iron. A wire will now carry eight messages each way, at the same time, without interference. What will not the more facile ether do?

Such are some of the first vague suggestions of a realm of power and knowledge not yet explored. They are mere auroral hints of a new dawn. The full day is yet to shine.

Like timid children, we have peered into the schoolhouse--afraid of the unknown master. If we will but enter we shall find that the Master is our Father, and that he has fitted up this house, out of his own infinite wisdom, skill, and love, that we may be like him in wisdom and power as well as in love.

We are a fighting race; not because we enjoy fights, but we enjoy the exercise of force. In early times when we knew of no forces to handle but our own, and no object to exercise them on but our fellow-men, there were feuds, tyrannies, wars, and general desolation. In the Thirty Years' War the population of Germany was starved and murdered down from sixteen millions to less than five millions.

But since we have found field, room, and ample verge for the play of our forces in material realms, and have acquired mastery of the superb forces of nature, we have come to an era of peace. We can now use our forces and those of nature with as real a sense of dominion and mastery on material things, resulting in comfort, as formerly on our fellow-men, resulting in ruin. We now devote to the conquest of nature what we once devoted to the conquest of men. There is a fascination in looking on force and its results. Some men never stand in the presence of an engine in full play without a feeling of reverence, as if they stood in the presence of God--and they do.

The turning to these forces is a characteristic of our age that makes it an age of adventure and discovery. The heart of equatorial Africa has been explored, and soon the poles will hold no undiscovered secrets.

Among the great monuments of power the mountains stand supreme. All the cohesions, chemical affinities, affections of metals, liquids, and gases are in full play, and the measureless power of gravitation. And yet higher forces have chasmed, veined, infiltrated, disintegrated, molded, bent the rocky strata like sheets of paper, and lifted the whole mass miles in air as if it were a mere bubble of gas.

The study of these powers is one of the fascinations of our time. Let me ask you to enjoy with me several of the greatest manifestations of force on this world of ours.

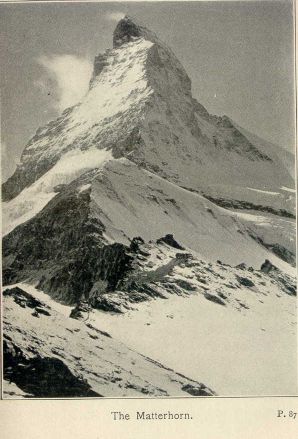

Many of us in America know little of one of the great subjects of thought and endeavor in Europe. We are occasionally surprised by hearing that such a man fell into a crevasse, or that four men were killed on the Matterhorn, or five on the Lyskamm, and others elsewhere, and we wonder why they went there. The Alps are a great object of interest to all Europe. I have now before me a catalogue of 1,478 works on the Alps for sale by one bookseller. It seems incredible. In this list are over a dozen volumes describing different ascents of a single mountain, and that not the most difficult. There are publications of learned societies on geology, entomology, paleontology, botany, and one volume of Philosophical and Religious Walks about Mont Blanc. The geology of the Alps is a most perplexing problem. The summit of the Jungfrau, for example, consists of gneiss granite, but two masses of Jura limestone have been thrust into it, and their ends folded over.

It is the habit, of the Germans especially, to send students into the Alps with a case for flowers, a net for butterflies, and a box for bugs. Every rod is a schoolhouse. They speak of the "snow mountains" with ardent affection. Every Englishman, having no mountains at home, speaks and feels as if he owned the Alps. He, however, cares less for their flowers, bugs, and butterflies than for their qualities as a gymnasium and a measure of his physical ability. The name of every mountain or pass he has climbed is duly burnt into his Alpenstock, and the said stock, well burnt over, is his pride in travel and a grand testimonial of his ability at home.

There are numerous Alpine clubs in England, France, and Italy. In the grand exhibition of the nation at Milan the Alpine clubs have one of the most interesting exhibits. This general interest in the Alps is a testimony to man's admiration of the grandest work of God within reach, and to his continued devotion to physical hardihood in the midst of the enervating influences of civilization. There is one place in the world devoted by divine decree to pure air. You are obliged to use it. Toiling up these steeps the breathing quickens fourfold, till every particle of the blood has been bathed again and again in the perfect air. Tyndall records that he once staggered out of the murks and disease of London, fearing that his lifework was done. He crawled out of the hotel on the Bell Alp and, feeling new life, breasted the mountain, hour after hour, till every acrid humor had oozed away, and every part of his body had become so renewed that he was well from that time. In such a sanitarium, school of every department of knowledge, training-place for hardihood, and monument of Nature's grandest work, man does well to be interested.

You want to ascend these mountains? Come to Zermatt. With a wand ten miles long you can touch twenty snow-peaks. Europe has but one higher. Twenty glaciers cling to the mountain sides and send their torrents into the little green valley. Try yourself on Monte Rosa, more difficult to ascend than Mont Blanc; try the Matterhorn, vastly more difficult than either or both. A plumbline dropped from the summit of Monte Rosa through the mountain would be seven miles from Zermatt. You first have your feet shod with a preparation of nearly one hundred double-pointed hobnails driven into the heels and soles. In the afternoon you go up three thousand one hundred and sixteen feet to the Riffelhouse. It is equal to going up three hundred flights of stairs of ten feet each; that is, you go up three hundred stories of your house--only there are no stairs, and the path is on the outside of the house. This takes three hours--an hour to each hundred stories; after the custom of the hotels of this country, you find that you have reached the first floor. The next day you go up and down the Görner Grat, equal to one hundred and seventy more stories, for practice and a view unequaled in Europe. Ordering the guide to be ready and the porter to call you at one o'clock, you lie down to dream of the glorious revelations of the morrow.

The porter's rap came unexpectedly soon, and in response to the question, "What is the weather?" he said, "Not utterly bad." There is plenty of starlight; there had been through the night plenty of live thunder leaping among the rattling crags, some of it very interestingly near. We rose; there were three parties ready to make the ascent. The lightning still glimmered behind the Matterhorn and the Weisshorn, and the sound of the tumbling cataracts was ominously distinct. Was the storm over? The guides would give no opinion. It was their interest to go, it was ours to go only in good weather. By three o'clock I noticed that the pointer on the aneroid barometer, that instrument that has a kind of spiritual fineness of feeling, had moved a tenth of an inch upward. I gave the order to start. The other parties said, "Good for your pluck! Bon voyage, gute reise," and went to bed. In an hour we had ascended one thousand feet and down again to the glacier. The sky was brilliant. Hopes were high. The glacier with its vast medial moraines, shoving along rocks from twenty to fifty feet long, was crossed in the dawn. The sun rose clear, touching the snow-peaks with glory, and we shouted victory. But in a moment the sun was clouded, and so were we. Soon it came out again, and continued clear. But the guide said, "Only the good God knows if we shall have clear weather." Men get pious amid perils. I thought of the aneroid, and felt that the good God had confided his knowledge to one of his servants.

Leaving the glacier, we came to the real mountain. Six hours and a half will put one on the top, but he ought to take eight. I have no fondness for men who come to the Alps to see how quickly they can do the ascents. They simply proclaim that their object is not to see and enjoy, but to boast. We go up the lateral moraine, a huge ridge fifty feet high, with rocks in it ten feet square turned by the mighty plow of ice below. We scramble up the rocks of the mountain. Hour after hour we toil upward. At length we come to the snow-slopes, and are all four roped together. There are great crevasses, fifty or a hundred feet deep, with slight bridges of snow over them. If a man drops in the rest must pull him out. Being heavier than any other man of the party I thrust a leg through one snow-bridge, but I had just fixed my ice ax in the firm abutment and was saved the inconvenience and delay of dangling by a rope in a chasm. The beauty of these cold blue ice vaults cannot be described. They are often fringed with icicles. In one place they had formed from an overhanging shelf, reached the bottom, and then the shelf had melted away, leaving the icicles in an apparently reversed condition. We passed one place where vast masses of ice had rolled down from above, and we saw how a breath might start a new avalanche. We were up in one of nature's grandest workshops.

How the view widened! How the fleeting cloud and sunshine heightened the effect in the valley below! The glorious air made us know what the man meant who every morning thanked God that he was alive. Some have little occasion to be thankful in that respect.

Here we learned the use of a guide. Having carefully chosen him, by testimony of persons having experience, we were to follow him; not only generally, but step by step. Put each foot in his track. He had trodden the snow to firmness. But being heavier than he it often gave way under my pressure. One such slump and recovery takes more strength than ten regular steps. Not so in following the Guide to the fairer and greater heights of the next world. He who carried this world and its burden of sin on his heart trod the quicksands of time into such firmness that no man walking in his steps, however great his sins, ever breaks down the track. And just so in that upward way, one fall and recovery takes more strength than ten rising steps.

Meanwhile, what of the weather? Uncertainty. Avalanches thundered from the Breithorn and Lyskamm, telling of a penetrative moisture in the air. The Matterhorn refused to take in its signal flags of storm. Still the sun shone clear. We had put in six of the eight hours' work of ascent when snow began to fall. Soon it was too thick to see far. We came to a chasm that looked vast in the deception of the storm. It was only twenty feet wide. Getting round this the storm deepened till we could scarcely see one another. There was no mountain, no sky. We halted of necessity. The guide said, "Go back." I said, "Wait." We waited in wind, hail, and snow till all vestige of the track by which we had come--our only guide back if the storm continued--was lost except the holes made by the Alpenstocks. The snow drifted over, and did not fill these so quickly.

Not knowing but that the storm might last two days, as is frequently the case, I reluctantly gave the order to go down. In an hour we got below the storm. The valley into which we looked was full of brightest sunshine; the mountain above us looked like a cowled monk. In another hour the whole sky was perfectly clear. O that I had kept my faith in my aneroid! Had I held to the faith that started me in the morning--endured the storm, not wavered at suggestions of peril, defied apparent knowledge of local guides--and then been able to surmount the difficulty of the new-fallen snow, I should have been favored with such a view as is not enjoyed once in ten years; for men cannot go up all the way in storm, nor soon enough after to get all the benefit of the cleared air. Better things were prepared for me than I knew; indications of them offered to my faith; they were firmly grasped, and held almost long enough for realization, and then let go in an hour of darkness and storm.

I reached the Riffelhouse after eleven hours' struggle with rocks and softened snow, and said to the guide, "To-morrow I start for the Matterhorn." To do this we go down the three hundred stories to Zermatt.

Every mountain excursion I ever made has been in the highest degree profitable. Even this one, though robbed of its hoped-for culmination, has been one of the richest I have ever enjoyed.

The Matterhorn is peculiar. I do not know of another mountain like it on the earth. There are such splintered and precipitous spires on the moon. How it came to be such I treated of fully in Sights and Insights. It is approximately a three-sided mountain, fourteen thousand seven hundred and eighteen feet high, whose sides are so steep as to be unassailable. Approach can be made only along the angle at the junction of the planes.

It was long supposed to be inaccessible. Assault after assault was made on it by the best and most ambitious Alp climbers, but it kept its virgin height untrodden. However, in 1864, seven men, almost unexpectedly, achieved the victory; but in descending four of them were precipitated, down an almost perpendicular declivity, four thousand feet. They had achieved the summit after hundreds of others had failed. They had reveled in the upper glories, deposited proof of their visit, and started to return. According to law, they were roped together. According to custom, in a difficult place all remain still, holding the rope, except one who carefully moves on. Croz, the first guide, was reaching up to take the feet of Mr. Haddow and help him down to where he stood. Suddenly Haddow's strength failed, or he slipped and struck Croz on the shoulders, knocking him off his narrow footing. They two immediately jerked off Rev. Mr. Hudson. The three falling jerked off Lord Francis Douglas. Four were loose and falling; only three left on the rocks. Just then the rope somehow parted, and all four dropped that great fraction of a mile. The mountain climber makes a sad pilgrimage to the graves of three of them in Zermatt; the fourth probably fell in a crevasse of the glacier at the foot, and may be brought to the sight of friends in perhaps two score years, when the river of ice shall have moved down into the valleys where the sun has power to melt away the ice. This accident gave the mountain a reputation for danger to which an occasional death on it since has added.

Each of these later unfortunate occurrences is attributable to personal perversity or deficiency. Peril depends more on the man than on circumstances. One is in danger on a wall twenty feet high, another safe on a precipice of a thousand feet. No man has a right to peril his life in mere mountain climbing; that great sacrifice must be reserved for saving others, or for establishing moral principle.

The morning after coming from Monte Rosa myself and son left Zermatt at half past seven for the top of the Matterhorn, twelve hours distant, under the guidance of Peter Knubel, his brother, and Peter Truffer, three of the best guides for this work in the country. In an hour the dwellings of the mountain-loving people are left behind, the tree limit is passed soon after, the grass cheers us for three hours, when we enter on the wide desolation of the moraines. Here is a little chapel. I entered it as reverently and prayed as earnestly for God's will, not mine, to be done as I ever did in my life, and I am confident that amid the unutterable grandeur that succeeded I felt his presence and help as fully as at any other time.

At ten minutes of two we were roped together and feeling our way carefully in the cut steps on a glacier so steep that, standing erect, one could put his hand upon it. We were on this nearly an hour. Just as we left it for the rocks a great noise above, and a little to the south, attracted attention. A vast mass of stone had detached itself from the overhanging cliff at the top, and falling on the steep slope had broken into a hundred pieces. These went bounding down the side in long leaps. Wherever one struck a cloud of powdered stone leaped into the air, till the whole mountain side smoked and thundered with the grand cannonade. The omen augured to me that the mountain was going to do its best for our reception and entertainment. Fortunately these rock avalanches occur on the steep, unapproachable sides, and not at the angle where men climb.